The Origins of Investment migration, that is offering residence or citizenship in recognition of a financial contribution to the government, predates far back as Ancient Greece. Within pre-modern Europe, it was relatively common to grant citizenship and residence in cities for a specified fee. Some of these pecuniary channels extended into the twentieth century, as was the case with Liechtenstein.

China

In the New World, across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, states offered citizenship or residence to those who invested – or promised to invest – in the country. One way that Chinese citizens could circumnavigate racist entry barriers to the US in 1888, for example, was to prove they owned at least $1,000 of property in the country.

United Kingdom

An important starting point for the current market in investment migration was the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision in 1984 to allow capitalist Hong Kong Island to revert back to communist Chinese rule. The result among Hong Kongers was a great demand for ‘exit options’, particularly in Canada, the United States (US), and Australia.

Canada

In 1986, Canada developed the Federal Immigrant Investor Programme (FIIP) out of an existing business investor program, which became the leading RBI scheme globally. Under the FIIP, investors were no longer required to be actively involved in running a business; they could simply make a passive investment of CAD$150 000

. Within a decade of the FIIP’s launch, the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and others developed or elaborated RBI programmes along similar lines to Canada’s option. Hong Kong became home to a flourishing ‘migration industry’ of businesses facilitating expatriation or exit options

Europe

Europe, too, has long hosted options for acquiring residence in exchange for an investment. When Malta gained independence in 1964, it launched the ‘Six-Penny Settler Scheme’, which aimed to encourage pensioners to spend their winters on the island and benefit from low income taxes. Participants had merely to purchase a property and prove a minimum annual income to qualify; the government did not assess physical presence in the country. This was further elaborated in 1988 into an early RBI program, ‘The Permanent Residence Scheme’, which enabled those purchasing or renting a property in Malta to gain permanent residence.

Spain

Spain in the 1980s allowed investors to gain residence by investing in a business or real estate project.

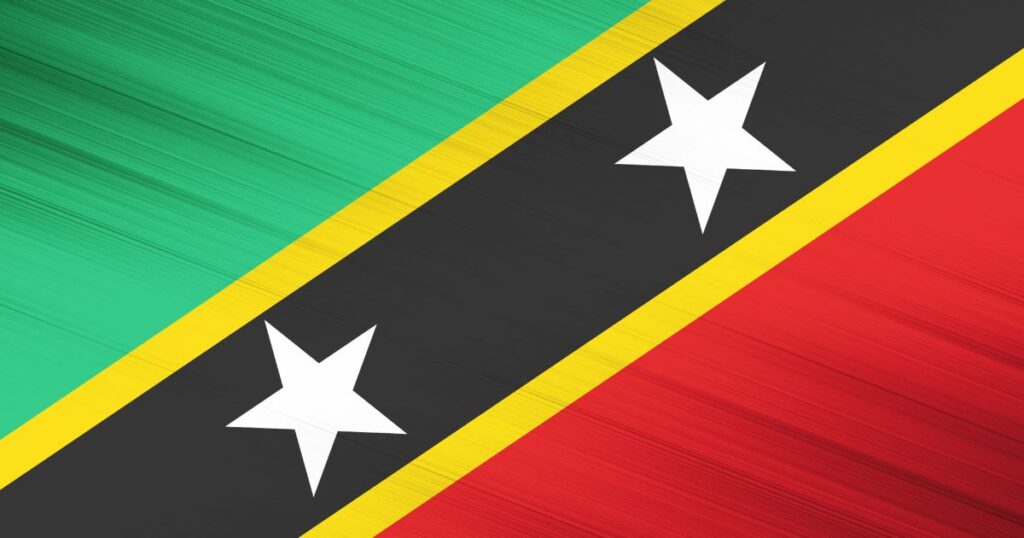

Early CBI in St Kitts

Modern CBI programmes are typically traced back to the legal provision Saint Kitts instituted in 1984, one year after gaining independence. The model for many contemporary programmes emerged in 2006 when a private firm revamped Saint Kitts’s offering into a more elaborated and formalized programme over the next five years. Changes included lengthening the application forms, increasing the information gathered on applicants, establishing a dedicated bureaucratic unit (‘Citizenship by Investment Unit’ or CIU) for screening applicants, creating a separate fund to hold and distribute the monies accrued through the government donation option, and appointing international due diligence firms to screen applicants. The Kittitian government also contracted the firm to advertise its program. The increased formalization – a division of labour for vetting applications and external oversight through due diligence checks that distanced the granting of citizenship from the executive branch – helped lower the risk flags raised at major accountancies, large banks, and other institutions. The result transformed the programme into an option that could be marketed more widely.

Within ten years, four other countries in the Caribbean adopted this model, revamping or starting CBI programmes, and the firm that worked with Saint Kitts extended a variant of the model to Malta. However, not all countries have followed this pattern.

Cyprus

In Cyprus, the government slowly formalized a CBI option from 2007 onwards, without contracting a private firm to design the program, out of a 2003 law enabling the government to grant citizenship for exceptional contributions to the country.

Turkey

More recently, Turkey in 2017 developed a very popular CBI programme designed within the government.

Source: Surak, Citizenship and Residence Schemes — State of Play and Avenues for EU Action.